A working group for exploring ways to respond to Generative AI in their teaching

The Faculty Working Group, Exploring Generative AI for Teaching and Learning took place over the 2023/24 academic year, funded by the University Council on Teaching and led by CDIL with support from the Center for Teaching Excellence.

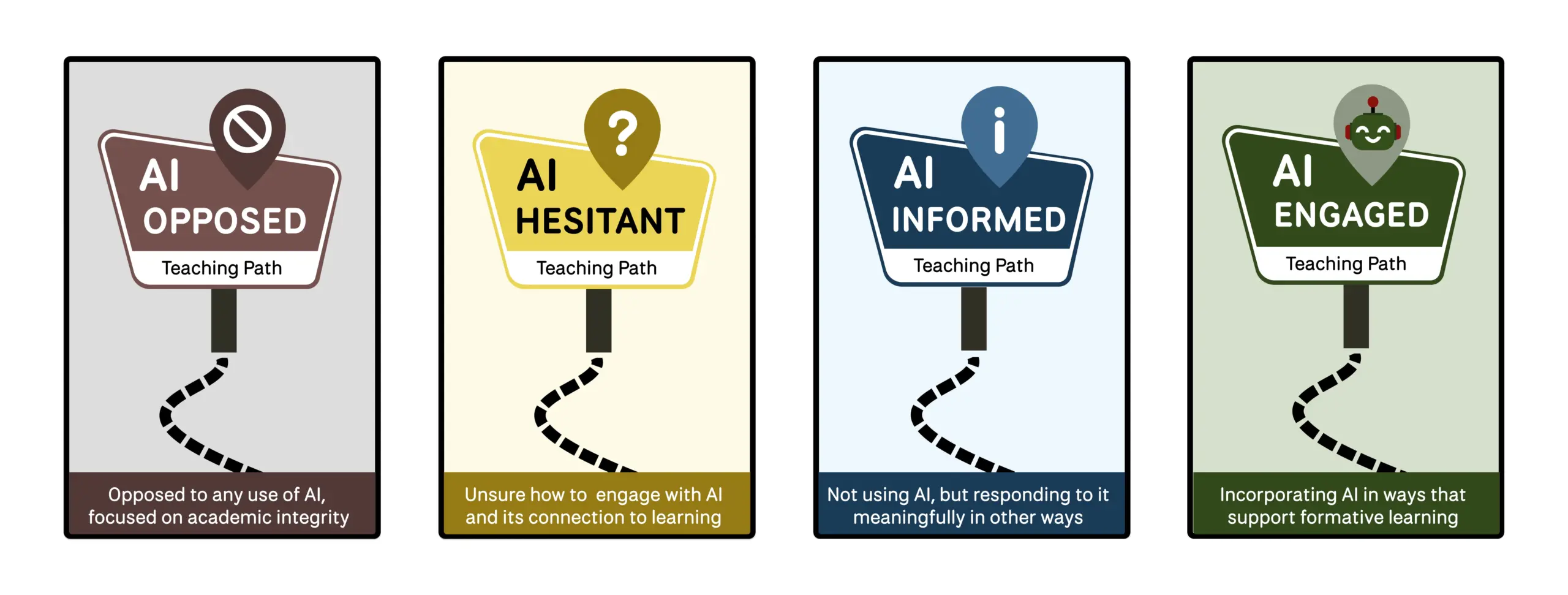

The Working Group’s focus was to introduce faculty to Generative AI and to assist in the development of approaches to participants’ Spring 2024 courses to accommodate whatever form of response faculty deem appropriate.

Generative AI tools have emerged over the past few months as a challenge to how faculty teach and how students learn in higher education. The working group did not require any prior experience with Generative AI and began with a hands-on introduction to the fundamentals of the technology. The working group provided guidance and support to participants as they developed approaches to Generative AI in their teaching practice.

Faculty shared their learnings with the wider BC faculty community to help others confront the challenge of Generative AI to their teaching practice, whatever form that might take.

Format

In this working group, participants focused on learning about Generative AI and designing their approach to it in the Fall semester. During this period, depending on the size of the project proposed, participants spent 2-4 hours per week of their time and met face-to-face every month, with additional meetings taking place with staff from CDIL and CTE as needed.

For the spring semester, the working group focused on implementing the changes in courses and gathering student feedback in a structured way to evaluate the efficacy of the digital learning experience.

The working group followed a similar format to others working groups facilitated by CDIL in the past two academic years. Faculty participants have reported that having the time, space, and support to think, practice, test, and implement ideas about their teaching practice with colleagues from BC has been of incredible benefit to them.

Participant Projects

Joy Field

Associate Professor of Business Analytics at Boston College’s Carroll School of Management

Prof. Field’s initial project asked students to work with Deloitte consultants on a mock strategic consulting project. After hearing from Deloitte about how the company is using AI, students were tasked with exploring how to use AI to create their own consulting reports and elaborate upon their process.

AI is a reality, and we need to harness it for good in our teaching. It is a powerful tool, but students need to be intelligent consumers of the technology, so AI can’t replace their understanding of the concepts and material (i.e., they’re synergistic). That’s where we, as instructors, need to position it and leverage its strengths (and acknowledge its weaknesses) to enhance learning.

Beth McNutt-Clarke

Assistant Professor of the Practice at the Connell School of Nursing.

With the guidance from CDIL and the feedback and discussion from the interdisciplinary group, I was able to come up with a meaningful and manageable project where students used specific prompts to have AI formulate a nursing plan of care, and then they critically examined the plan for strengths and opportunities, followed by a discussion of the use of AI in healthcare.

I want my colleagues to know that AI tools can be useful for many purposes. They have strengths and limitations and seem to change and develop with each passing week. They can be a great complement to learning. It is helpful for faculty to be aware of what AI can do, how it can be used in a course, and how students may be using it.

Catherine Conahan

Assistant Professor of the Practice at the Connell School of Nursing

Prof. Conahan’s project asked students to develop a literature review using Elicit. While her project hasn’t changed, she feels more confident in using and teaching AI to her students.

I have learned that keeping up with AI developments is almost impossible. Staying abreast of good and bad developments takes continuous updates and ideally being part of a group like this one.

Tony Lin

Assistant Professor of the Practice and the Russian/Slavic Coordinator in the Department of Eastern, Slavic, and German Studies at the Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences

Prof. Lin came to the group as he was interested in using AI to teach and learn Russian (and foreign languages in general). He wanted to know what AI is good at when/if it falls short, and in what particular instances.

AI doesn’t make certain kinds of mistakes, such as spelling or punctuation. In general, it is a very good resource, provided one knows how to use it and knows when it is wrong or “hallucinating.” My message to colleagues is that AI is here to stay, so it is our imperative to figure out how to co-exist with it peacefully.

Elisa Magri

Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences

Prof. Magri joined the group to learn more about how AI works and is evolving. Her project was meant to be a more engaged analysis of why AI can’t work in the classroom.

Elisa wants to remind others that we need to learn more about AI before making policies about it. At the same time, I am convinced that we need to find the best ways to explain to students how AI can negatively impact their learning, interpretative, and critical skills.

Timothy Muldoon

Associate Professor of Philosophy at the Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences

Prof. Muldoon came to the group with the same goal as many others—to learn how to prevent students from using AI. However, after participating in the group, his goal is now to encourage students to use AI positively and ethically.

AI—It’s a tool. It can be used wisely and it can be used poorly or unethically. Our students are ready for guidance on how to use it wisely and well.

Joan Ryan

Part-Time Faculty in the Master of Science Leadership Program at the Woods College of Advancing Studies

Prof. Ryan joined the group hoping to learn more about dealing with students who use AI. After joining, she changed her focus to creating assignments where students can learn to use AI responsibly, which adds to their learning rather than short-circuits it.

Of her experience with AI and what she would like others to know, Joan says:

There are many creative ways to show your students responsible and practical AI usage. It is a reality and we have to learn to deal with it — we can treat it as a tool and work with our students from that perspective while still offering high-quality opportunities to learn.

Arvind Sharma

Assistant Professor of the Practice in Applied Economics at the Woods College of Advancing Studies

Prof. Sharma had hoped to think more deeply about how instructors should adapt their courses, that is, to develop best practices to inform the rest of the BC community about tackling developments caused by GenAI.

Be willing to learn from others, but do not discount your gut feeling.

Implement what makes the most sense to you (and is still manageable), as you know your subject-student dynamics and other constraints better than anyone else.

Incremental accommodations are fine, but instead of radical changes, keep on learning so that you stay relevant over time.

Tristan Johnson

Associate Dean for Graduate Programs at the Woods College of Advancing Studies

Associate Dean Johnson came to the group hoping to learn better ways to use AI effectively in teaching settings. He learned the differences between general AI and generative AI and narrowed down how he could use them in his teaching.

Tristan wants others to know that discussion with others [about AI] is important.

Vanessa Conzon

Assistant Professor of Management and Organization at the Carroll School of Management

Prof. Conzon was drawn to the group because she was interested in potentially restructuring her final exam in light of AI. She was inspired by others in different disciplines who used AI in their projects and classrooms.

Vanessa would like others to know that AI varies drastically between disciplines.

Dana Sajdi

Associate Professor of History at the Morrisey College of Arts and Sciences

Prof. Sadji’s curiosity about GenAI drew her to participate in the working group.

I became much more sensitive to the “process” of teaching and learning rather than the idea that students learn by trial and error and by “osmosis” and that evaluation is measured by the quality of analysis and writing in essays and papers.

I learned that making an immediate or necessary connection between ChatGPT and Academic Integrity is a grave mistake. It is possible but not necessary.

Fang Lu

Associate Professor of the Practice in the Department of Eastern, Slavic, and German Studies

Prof. Lu joined the working group and was interested in exploring how students might appropriately use GenAI to support their Chinese language learning.

Fang recommends that her colleagues:

- Encourage open dialogue with students regarding the use of AI in language teaching.

- Develop guidelines for using AI within our specific courses, tailored to various levels of language proficiency.

- Redesign homework to leverage AI for supporting learning.

- Create assignments aimed at encouraging students to practice caution when using AI tools.

- Redesign the tests and exams to introduce greater challenges, with the aim of enhancing students’ judgment and competence in language learning.

George Wyner

Associate Professor of the Practice of Business Analytics at the Carroll School of Management

Prof. Wyner thought he would develop ways for students to experiment with different prompts for ChatGPT but shifted his focus to developing a custom chatbot, which he called a “stuck bot.” The “stuck bot” helps students focus on the process of “getting unstuck with technical problems” and then reflect on that experience.

AI can be a tool for learning. It is tempting to go on defense in the face of AI, but exploring what it might do in the classroom changes one’s whole perspective. Using AI effectively does not require a computer science background. Dive in and give it a try! Look at what others are doing!

Kathleen Bailey

Professor of the Practice of Political Science at the Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences, Director of the Gabelli Presidental Scholars Program, and Director of the Islamic Civilization and Societies Program,

Prof. Bailey initially wanted to use AI to help her students compare two complex readings. After participating in the working group, she left thinking deeply about the role that writing plays in helping one organize one’s thinking.

I think AI should be used very sparingly. Don’t succumb to the idea that AI is here to stay and that we just need to train students to be “prompt engineers.” The frustration of ordering one’s thoughts and writing them eloquently is an essential part of being human. We are doing students a disservice if we remove assignments that force students to master the material and think deeply about a topic or issue. Doing so robs them of the pleasure that comes from creativity and self-knowledge.

Lauren Wilwerding

Assistant Professor of the Practice of English at the Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences

Prof. Wilwerding wanted to reflect on how to design best a close reading prompt for core students in a post-AI classroom. She initially focused on incorporating AI but changed gears and instead worked on changing her assignment to reflect authentic learning principles.

[Authentic Assignments] are challenging to create and were considered SOTL best practice before Sept 2022, are also assignments that AI can’t do especially well and students are more motivated to engage with themselves. Dana and I had a conversation where we both observed that the types of questions and creative changes we were bringing to our teaching during the group mirrored the ways we approached teaching in the first semester after COVID-19. In other words, either intentionally using AI or designing classes and assignments that intentionally avoid AI doesn’t require reinventing the wheel but refreshing on the science of effective teaching and learning.

Mary Ann Hinsdale

Associate Professor of Theology at the Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences

Prof. Hinsdale’s initial plan was to develop an assignment that asked students to complete a critical investigation of AI for the classroom.

Don’t reject it out of hand, but think through your teaching policy regarding the use of AI. For my theology classes, it is most useful in bibliographic research.

Naomi Bolotin

Associate Professor of the Practice of Computer Science at the Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences

Prof. Bolotin entered the group with questions about how well ChatGPT could do with a coding problem. Her project idea included having students solve a problem in Python, then having ChatGPT solve it, and comparing the two approaches in terms of what they learned.

As for a takeaway that she’d like to share with others, Naomi states that discussing teaching-related topics with other faculty, particularly an issue as seismic as generative AI, is very helpful. Generative AI is radically changing how students learn and how we will need to teach going forward.

Paula Mathieu

Associate Professor of English at the Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences

Prof. Mathieu designed a new Literature Core course centered around the question, “What makes us human?” The course, Monsters, Martians, and Machines, intentionally engaged with literature connected in content and form to generative AI.

I would like my colleagues to know several things about AI:

- Students can and should be engaged in a shared inquiry about AI in higher education. I believe students should be part of the conversation to determine appropriate and inappropriate uses of AI, explore what tasks are central to learning (and are worth struggling over), and what can be usefully offloaded to machines. People who are college students today will be determining AI policy and parameters in the future, so we need to engage them now so they care about the practical, ethical, environmental, and social aspects of algorithms and AI.

- The use of ChatGPT cannot be proven, so accusing students of AI use seems both pointless and potentially very harmful. I have heard several students remark that they or someone they know were accused of using AI when they didn’t. Instead, I think a conversation about what caused your concerns as a reader should be discussed: this paper isn’t exactly addressing the topic; the language here is rather redundant and flat–it almost sounds like a robot wrote it; the claims here are overly general; the textual evidence is either missing or isn’t accurate, etc. All those issues are real problems by themselves, whether or not students used AI to write the paper. But accusing students operates from a situation of distrust and risks damaging one’s working relationship. I think faculty members need to stop operating out of a position of reactivity, suspicion, and fear and challenge themselves to adapt their own teaching to this moment. This might mean different kinds of assignments, more process steps, and, when appropriate, directly engaging with AI in ways that shed light on our course content. I hope it does not mean a retreat into blue books, paper quizzes, and a deficit model of education. This is a challenging moment in education, but one we can meet if we engage in meaningful co-inquiry with our students.

- Everything is in process, so we need each other and humility. What I don’t know about AI far outpaces what I do, and that trend will continue. But that doesn’t mean we should throw up our hands. Instead, I am inspired to pay attention, engage with others, listen more than I talk, and be open to learning about new opportunities and concerns related to AI.

Vincent Cho

Associate Professor of Educational Leadership and Higher Education and Program Director of the Educational Leadership/Professional School Administrator Program at the Lynch School of Education and Human Development

Prof. Cho initially joined the working group, thinking about how he might use GenAI to coach students in their writing. The working group helped him “parse out [his] ideas into distinct objectives and sets of goals” and narrow his focus to “helping students generate ideas and logical arguments before writing.”

There are many forms, platforms, and uses, and we have a responsibility to be forward-thinking in helping students navigate appropriate use.

Virginia Reinburg

Prof. Reinburg came to the working group with the goal of redesigning her undergraduate history courses and improving her pedagogy for the new landscape of GenAI.

Inspired by George Wyner’s “stuckbot,” I experimented with creating a history chatbot to support students in my undergraduate research course on “The Study and Writing and History.” My goal was to break down the steps of identifying a research topic and historical question for investigation, and to help students practice coming up with research topics. I ultimately decided not to use the chatbot, in part because there was not enough time to develop it into a tool that did not write an entire research paper for the user. But more importantly, offering it to my students increasingly seemed like an evasion of my responsibility to help them learn how to structure a research project. I am even more skeptical of the use of GenAI in undergraduate humanities courses than I was before I participated in the working group. I would like my faculty colleagues to know that we need to keep reckoning with AI as it evolves, and with our students’ engagement with AI. It’s not a topic you can master in a two-hour CTE or CDIL session.